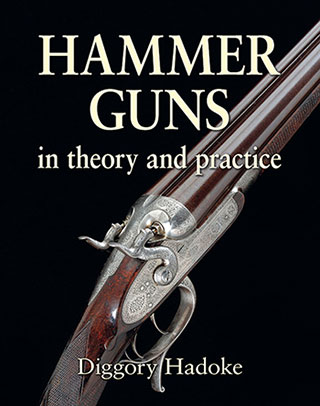

There is something rather iconic about Stephen Grant’s hammer guns, especially those with the side-lever operating mechanism that became Grant’s trademark, not only in the hammer gun era, but well into the twentieth century, when he used it on some very elegant side-lock ejectors (‘though they had quite tricky ejector work!).

People sometimes ask why he stuck with side-levers, when most of the trade used top-levers for their snap-action guns. I have a pet theory that many of the gunmakers then in business really did not want to pay royalties to their rivals, if they could manage not to. By 1865, the Purdey bolt and Scott spindle were teamed up neatly and Purdey and Scott had equally neatly tied them up with patent protection. Any London gunmaker wanting to use the combination to make a top-lever, breech-loader had to pay Purdey two pounds. Birmingham gunmakers had to pay W&C Scott.

Grant probably paid the patent fees for the Hodges patent of 1871, (universally known as the ‘Grant & Hodges Patent’), upon which his best known side-lever hammer guns are made. That meant no cash to Purdey or Scott! However, once the patents had lived their maximum fourteen year life-span, Grant started making side-lever guns with Purdey bolts.

Perhaps his liking for the side-lever, which had become something of a trademark, remained but he realised that using a simple Purdey bolt, rather than the Hodges patent, with its more complex treble-bolting system was preferable and easier to make. Perhaps a customer simply asked for it to be made this way. Whatever the reason, we encounter a few late-model Stephen Grant side-lever hammer guns with Purdey-bolt locking only. Very well they work too!

The gun illustrated is one such example, which I picked up in poor condition and decided to keep for myself. At first it looked like a bit of a gamble. To make the scope of the project clear, I’ll outline what was wrong with the gun when it arrived: The barrels were badly pitted, very badly, in fact. They were also slightly bulged in one tube, and there were dents all over them. The ribs were loose. The loop was loose. The bite was worn and the right mainspring was broken. There were some awful dents in the stock, notably either side of one lock-plate and another hum-dinger in the middle of the forend. The frond bead was missing. Overall the gun was dirty and the engraving on the trigger-guard and strap was badly pitted and worn.

What I liked about the gun was its obvious quality, that it seemed relatively little used and that it was a16-bore, a gauge that I like very much; and a bar-action with rebounding locks. Most of these Grants are back-action hammer guns. Sometimes a gun speaks to you; this one was shouting! I decided that it probably wouldn’t be a candidate for re-proof, as it was unlikely I’d get all the pits out. Personally, I can live with a bit of pitting and would rather have thicker walls with a few pits than shiny bores and thin walls. That meant, if I was going to fix the gun up, it would be for personal use, not as a commercial proposition.

First I went to see Scotty, the barrel maker. He had a peek down the bores, listened politely to my prattle and said ‘What’s the point?’ Still, he owed me for a couple of rifles I had passed his way and he was happy to have a go in return. He lapped out a good deal of pitting, stripped ribs and loop, re-laid those and struck-up the barrels; beautifully, as he always does. Then I sent them to John for browning, but not before the engraving on the rib and the lettering had been picked out cleanly. John got the brown as close to original as possible and we were in business. Somehow, we had a pair of straight, clean barrels that still retained well over twenty-eight thou’ in wall thickness, despite a few stubborn pits, and now looked more than passable.

Then to the mechanical side of the conundrum. Ask someone to make you a new mainspring and watch them laugh you out of the room or throw something at you. Not just any mainspring, this had to be top quality, made from scratch and matched perfectly to the pressure of the other lock. Dave, my finisher called in a favour (from whom I still don’t know) and a few weeks later the Grant came back with a perfect new mainspring. Happy days. Dave then stripped the gun completely, boiled off the action and metal parts in soda and they came out remarkably well, with lots of original colour on them. The trigger guard was the exception and it took the engraver two days to completely re-cut the worn scrolls, numbers and borders. That was then blacked.

Dave kept calling me to say how much he loved the gun and what superb quality it was, with its beautiful John Stanton locks. As per my instructions, Dave gently cleaned out the chequer, retaining the flat-top original pattern, which was remarkably un-worn. He lightly dressed the drop points and removed the dents where he could. I did not want to plug any, I’d rather live with the odd blemish where it does no harm.

Once the wood was cleaned up, a few coats of red oil brought out the lovely figure. I will oil finish the gun myself, using an old oil recipe I cook up from a book in my library. I deliberately left many parts as they were, rather than polish and black them. I don’t like my guns to look too ‘tarted up’ and I think trying to remove every trace of a gun’s past life is a shame.

To fit the gun to myself, I had Dave file-up a Silver’s pad and leather cover it, giving me a good 14 3/4” to centre. With that done, I was pleased to see that, when I brought it the shoulder, my sight picture was exactly as I like it; straight down the rib.It was a relief not to have to put any bend or drop adjustments on. I even managed to find an old Stephen Grant hammer gun case, with label, which just needs re-blocking.

What I now have for my own pleasure is an 1883 Stephen Grant 16-bore side-lever hammer gun with 30 1/4” Damascus barrels, 2 1/2” chambers, choked about Improved Cylinder in both barrels. The stock is straight hand, with lovely figure and the gun, to my eye, is spot-on.

I used the Grant with a fair deal of success during its first season. This week, in early July, I picked it up and headed for a local sporting clay shoot with some friends, having not really shot since January, yet posting a respectable 45 out of 50 and feeling the gun working well for me. Everyone has their own ideals when looking for a gun but they rarely manifest themselves entirely when trying to find something vintage that ticks all the boxes. For me, this is just about perfect. The heavier than average weight is spot-on, the gauge provides the scale of action I like, the bar locks and side-lever are my preference and the quality is top-notch.

It seems I can also shoot quite well with it, which after-all is a big deal. I have let plenty of pretty gun slip through my hands because I didn’t like the way they shot for me. I think this one is a keeper.

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on (modified )