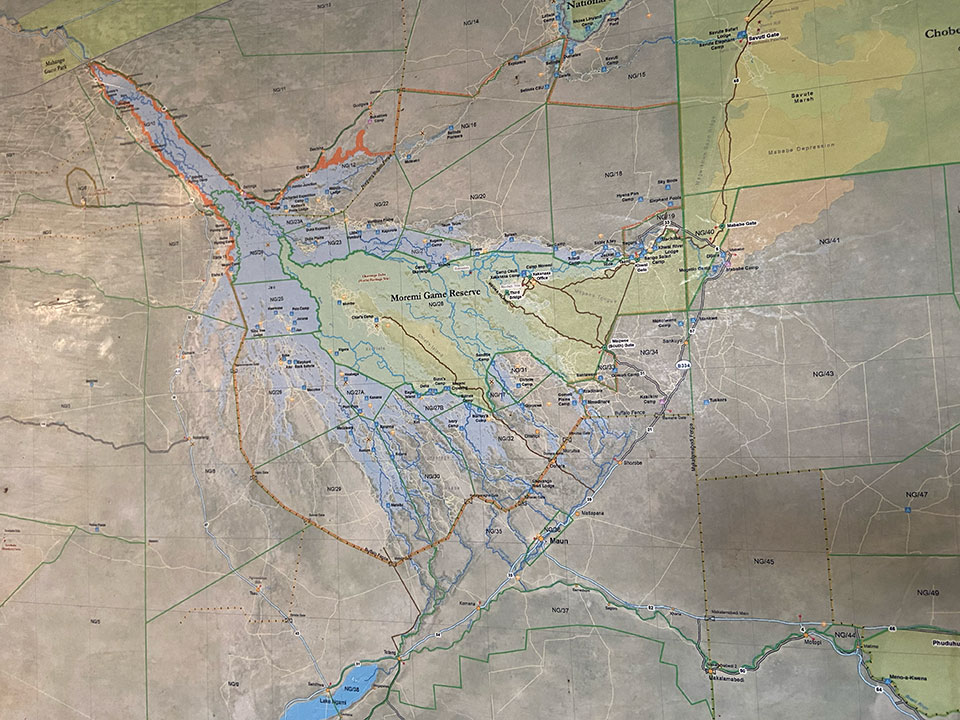

Returning to Botswana after seventeen years was an experience. The country has changed a lot in the intervening years, with an anti-hunting President installed for much of it. This led to a wholesale ban on hunting in the country, on government land.

That regime has now ended, with the former President and his brothers in self-imposed exile in South Africa, fearing prosecution for alledged widespread corruption and theft during their tenure, should they return to Maun.

With a new government installed, a resumption of hunting began. The current President is very much interested in the sustainable sport hunting system as a means of both protecting, and creating revenue from, Botswana's rich wildlife resources.

However, much has changed since 2007 and the old Splash Camp we hunted from in the Okavango Delta is no longer open. The entire Delta is now a World Heritage Site and no hunting is allowed within it.

Instead, we hunted one of the adjoining concessions, now run by Savannah Sky Safaris, owned and operated by old friend Grant Albers, with whom we hunted last time, and Richard Peake, a Botswana native and himself the son of renowned professional hunter, the late Neville Peake.

The terrain we hunted in early May 2024 was dry and barren, unlike it will be later in the year, when the water begins to run from Angola, filling the lower ground with fresh water channels, leaving islands of higher ground covered with thick vegetation.

There is nothing available to hunt here except elephant, so this time we were unable to take detours to shoot impala and warthog for the pot or pursue guinea fowl and francolin in the evenings. Later in the year, there is good duck shooting, when they follow the water's advance into the newly forming lagoons and make a temporary home here.

Our daily routine was to leave camp after breakfast, at around 07.30, and mount the Land Cruiser, slowly traversing the dusty tracks around the million-acre concession, scanning the bush for either tracks in the sand that suggested the recent passing of a big, old bull or looking for actual elephants through the mopane and ironwood thickets.

A promising track would cause us to stop and head out on foot to follow them until we found the elephants browsing or resting in thick cover. Then, we would try to keep down-wind of the quarry and get as close as possible in order to assess the age and the quality of the ivory each animal displayed.

The most productive times were early morning, before the real heat of the day arrived and caused the elephants to seek thick cover, where they would remain hidden until they once again veturred out in the late afternoon.

We were in camp for ten days and I was hunting with old friend MJ, from Texas, who had previously shot an Okavango Delta elephant with ivory weighing just over 70lbs each tusk. He hoped to better this time and Grant had said it was certainly possible, having bagged several elephants in the previous two seasons with ivory in the high eighties, and even a couple of ninety-pounders.

Neophyte elephant hunters might wonder what the big deal is about the size of the ivory. After all, you cannot sell it or even give it away (unless to a direct decendent or museum). The ansewer is that hunting is a quest. The hunter sets himself parameters and applies them to his hunt. We saw upwards of fifty bulls every day and MJ could have easliy shot one on the first morning of the hunt. However, we were there to hunt, not to kill and MJ was quite prepared to go home without having fired a shot if the right animal could not be found.

Old elephants eventually die of starvation or illness through severely weakened bodies, ravaged by lack of nutrition. Their last set of teeth wears out and they are no longer able to chew and process the enormous quantity of low quality fodder they spend all day browsing.

Our quest was to hunt and shoot an old bull who was on the cusp of degeneration. By doing so, we hoped MJ would take home a nice pair of tusks as mementos and the old bull would be spared the long, slow, painful death that was, otherwise, to be his fate.

Elephant hunting is hard work. The ground is hard, the sun is hot, there are thorns and snakes and lions and buffalo that might at any time liven up your morning, not to mention the challenges of a herd of aggressive cows or the charge of a teenage bull enraged by 'must', a period of intense hormone generation in males that makes them want to fight everyone they encounter, as they seek to vent their sexual urges.

Our trackers were masters of assessing the footprints of elephants in the sand. They could age and size a beast from the track and determine how long ago it was made, then follow it over soft ground or hard. When it became mixed with the tracks of other elephants, they could stay focussed on the right track, having memorised its features, as every one is like a fingerprint and unique in its own way.

The terrain varied and sometimes we were lucky enough to see elephants in open ground, where assessing their age and ivory was easy. However, more often, we had to follow them into thick cover and get within ten yards or so before we could get a proper look. It is incredible how close you can get to an elephant without him knowing you are there.

With the wind blowing steadliy, staying down-wind and moving slowly and quietly, we tracked elephants a couple of miles or more, got to within a few feet of them, as they stood under a shade tree, assessed the animals, then moved off; all without ever being detected or even suspected by the quarry.

The first few times you do this is terrifying, as the sheer size, power and unpredicatability of the elephants is awe inspiring. With experience, you learn to recognise the signs of an elephant that is relaxed, or suspicious, timid, agitated or aggressive. The trick is to stay alert without overdosing on adrenaline with every encounter. The whole experience is rather primeval and you certainly know you are alive and functioning at a level of sense and emotion that is not often encountered in our safe, regulated modern lives.

Hunting in this concession highlighted the reality of much, probably most, of Africa. We were outside the Delta, which is protected from human encroachment, habitation and hunting. Here, we were mixing with the inhabitants of small villages, their cows, donkeys, horses and goats.

The biggest threat to wild Africa is human-animal conflict over space and resources. The people here are subsistence farmers. They are not allowed to hunt but they do. Firearms ownership is widespread and legal. Farmers are allowed to shoot animals to protect their crops and do so daily. While the animals of the Delta we saw in 2007 were plentiful and visible, here, they were far more nocturnal and skittish.

While hunting, we came across several incidences of poaching that had occurred hours before our arrival. A young giraffe shot, skinned, gutted and removed on horseback one day, a Cape buffalo bull shot at close range in the face by a load of buckshot, skinned and moved out by truck another.

Legal and regulated hunting outfits like ours also act as the eyes and ears for the Game Wardens, who we informed of each incident and they then investigated. It is a constant battle. Poachers, of course, are indisriminate and will kill anything they can find. To them it is just meat or money.

As the week wore on, it became increasingly stressful for the trackers. They are competitive and proud. A successful hunt gains them kudos among their peers. Failure invites ridicule and loss of face. They were very motivated to find a good bull and with each passing day, they felt more pressure.

By day six, I started a joke as we entered camp in the evening, still without a shot having been fired. "Is your lucky number seven?" I asked the head tracker. "Lucky seven, yes," he laughed.

We then had our customary couple of beers, a cigar and a three-course meal, cooked with pride by our camp cook and served by her companion, with a degree of ceremony and formality that belied the remote setting. This is all part of the unique charm of a hunting camp in Africa.

Day seven came and went, "Lucky Eight" we joked as we headed home and the light began to dim. The next day we saw a lot of elephants; probably close to one hundred in total, many cows and young bulls, which group together with the babies and calfs in protective herds, from which mature males are excluded.

At midday we would retire to a shade tree by a lagoon and dine as the sun beat down and the elephants came to drink, the hippos would fart and fight noisily in the receding pools of water and crocodiles would cruise patiently looking for an opportunity, like the body of a baby hippo, killed when two large males clashed and crushed him between them.

We saw a baby elephant without a tail (removed by lions or hyenas) who had been adopted by a posse of young bulls. He had clearly become estranged from his mother and had latched on to the teenagers, who very obviously wanted to get rid of hm. They approched a herd of cows and calves drinking at the lagoon and pushed junior to join them, which, eventually he did and the bulls quietly slipped away, leaving the baby in the care of the women. It is likely that one of the nursing cows would let him feed and adopt him.

By day nine we were starting to think it was a distinct possibility that we were going to have to contemplate going home without firing a shot. MJ was relaxed about it and PH Grant was doing his best to appear relaxed but he wasn't, which we all found very funny.

He saw it as his responsibility to find a suitable elephant and was looking at the possibility of failure for the first time in his thirty year career. Another client would have been chewing the furniture but MJ was not that kind of client. This is hunting, not killling. To a true hunter, every day is beautiful. Every experience worthwhile, every failure a learning experience.

We would continue to get up in the morning, track elephants and see what fate delivered. As we smoked a cigar and MJ ate all the popcorn, around the fire-pit that night, chatting about the day, the sounds of the night, the experiences Africa had served up to each of us over the years and during the week, we are all living the dream. A dream of hunting wild Africa in a way that 99% of humanity will never experience. It felt good to be alive.

We went to bed in our tents that night, sunburned, scratched and aching from a hard couple of weeks hunting on the hard ground under a hot sun wondering what the last day would bring. I slept well. I suspect Grant did not.

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on