William Oliver Greener and his brother, Charles, published a controversial book in 1907 titled "The Causes of Decay of a British Industry," under the pseudonyms "Artifex" and "Opifex." The book analyzed the causes of decline in English gunmaking and the rise in foreign manufactures.

Graham Greener (of the famous Greener family of gunmakers) in his "The Greener Story," comments that his ancestors' book "should have been more widely read by politicians and the captains of British industry." He wrote: "If this book had been more widely read perhaps England's cycle and car industry would not have followed this decline with remarkably similar results."

Recent debates in various sporting magazines concerning the qualities of English versus foreign guns suggests a larger question: why has the British gun trade declined so precipitously that more Englishmen use Italian or Japanese guns than British, and that British guns are virtually unseen in America?

Prior to World War I, English guns were commonly imported to America: Greener and W.&C. Scott were as well-known to Americans as Parker and Remington. Now Purdey (owned by the Swiss firm Richmont), Holland and Holland (owned by Chanel) and some few other quality British makers represent the British in America, albeit among wealthy sportsmen.

Post-World War II, British cars dominated foreign sales in America (as well as on the continent); today Rolls-Royce is owned by BMW, Bentley belongs to Volkswagen, and Jaguar Land Rover are part of the Tata organization.

And car and gun manufacturing are not alone in this decline: British industry in general suffer from a demise of primacy in world manufacturing. The basic cause is the failure to invest in the modernization of British capital equipment with the consequent loss of competitive power.

This failure in turn is the result of government policies which, for the sake of short term aims, sacrificed the future by deliberately inhibiting investment.

At the end of the last war, Britain emerged as one of the victorious great powers helping to shape the peace, ahead by far of the war-shattered economies of Europe. On the continent, only Sweden and Switzerland were better off; elsewhere, only the United States and Canada.

Britain was among the leaders in the world in the high-tech industries of aircraft, electronics and vehicles; it had a solid and traditional foundation.

But success quickly turned to failure. After having led the world for 200 years, Britain was no longer counted among the economically most advanced countries. The popular slogan of the 1960s aptly summed up this complacency: “we never had it so good.” The catching-up process by Europe was ignored and the lead by America was taken for granted.

At the heart of the British malaise was the myth that it was shortage of demand rather than the inability to expand...

While Japan, the United States and the rest of Europe were scrambling to produce guns for sportsmen, English gunmakers took a kind of pride in “waiting lists.” At the heart of the British malaise was the myth that it was shortage of demand rather than the inability to expand supply that set the tone for the prestige end of the market. Like gunmakers, Rolls-Royce, Jaguar and others had waiting lists running into years rather than months. In 1980, a time of massive unemployment and heavy losses by British Leyland, delivery time for the Land Rover was 14 to 17 months. The problem was the inability of the company to find investment funds necessary to increase production at a time when Land Rover had a virtual monopoly of 4x4 vehicles worldwide. It has been said that Toyota’s Landcruiser would not have been launched but for this continually unfulfilled demand for Land Rovers.

From start to finish, a pair of best guns takes eighteen months to make. Holland, Boss and Purdey obviously cannot compete with the Italian and Spanish makers who can turn out a quite suitable gun in a fraction of the time using modern automated machining and finishing techniques. Is it any wonder that the best British guns are made primarily for collectors, not used in the shooting field?

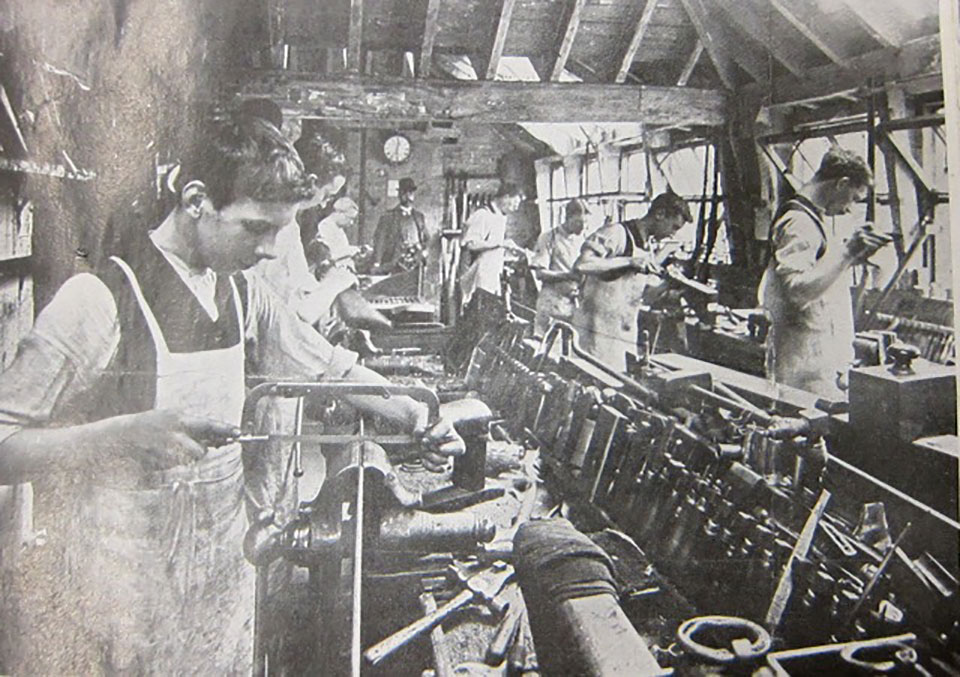

And what of the mass market makers? They do not exist in Britain primarily because they were unable to secure the investment for high-tech production methods in order to compete worldwide. Successive British governments – Tory and Labour – over the past sixty years have failed to set the necessary preconditions for investment in British industry. The emphasis of the Treasury and the Bank of England have been on complex monetary, fiscal and other policies to deal with issues such as trade deficits, the value of the pound sterling and inflation. To rectify these problems, the choice was the easy way out: cutting investment, innovation and improvement in basic British industries. The concern, in short, was in redistributing the economic cake rather than increasing its total size. Gunmakers, along with other manufacturers, shared the legacy of traditional industrial locations, out-of-date lay-outs and antiquated equipment.

The main problem is to divert enough resources from consumption to investment...

The quality of British engineering is still as good as that of Europe, Japan and America. Labour skills too compare favorably with those of their rivals. The financial and legal system, the law-abiding nature of the British people – all of the important preconditions for a successful economy exist. The main problem is to divert enough resources from consumption to investment, and to expand the capital goods industries to supply the necessary machinery and tools on which a prosperous economy depends.

The victims of the government’s misplaced emphasis on financials (inflation, balance of trade, etc.) are the capital goods industries, engineering, machine production, steelmaking, building – and gunmaking. The result will be the continued acquisition of British companies by foreign investment and the inevitable decline of traditional industries. This trend can be reversed, but years will be required for companies to acquire the necessary machine tools, for unions to realize that technical progress will enhance, not undermine their skills, and, most important, for policy makers to reverse the course that they have been following which has resulted in the devastation of much of Britain’s industrial strength. Perhaps then British gunmakers will catch up with the rest of the industrialized world and contribute fully to the productive part of the economy.

Daniel P. King is a political economist, a member of the Arms and Armour Society, and the proud owner of British guns including Holland & Holland and W.&C. Scott.

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on