There are few old gun’s for whom I don’t have a soft spot. Be it a lowly provincial boxlock of average quality or a strange 19th century patent that never really worked out, but illustrates the brilliance of the inventor who thought it up and got his idea into production. They all have a charm of their own and are fun to play with.

However, over the years, there is one, very cleverly conceived and beautifully made side-lock, by a top class maker that I have never learned to love. It is the spring-cocking assisted-opener, known in many gun dealing circles as ‘The Wristbreaker’, usually found bearing the maker’s name ‘Charles Lancaster’ on the locks.

While I appreciate the cleverness of the design, bow to the genius of the designer who conceived it and am humbled by the skill of the men who made it, I just can’t say I ever liked shooting one, nor wanted to own one.

Before I get started, let’s just make the note that my feelings are by no means universal. I’m not going to try and convince the reader that this is not a good gun, nor that it should be avoided by vintage gun enthusiasts. In fact, the reverse. If a reader examines one and likes it, I would recommend he buy one; because they are relatively inexpensive and represent enormous value for money.

I’d go as far as to say they represent probably the best value in terms of interesting design, complexity of mechanism, difficulty to build and generally encountered quality that you will find in a side-lock by anyone. No, this difficulty in learning to love this particular gun is peculiar to me, though the value of them on the market suggests that, if people are voting with their wallets, my sentiments are not unique.

‘the locks are cocked before ejecting and no extra force is required to open the gun’.

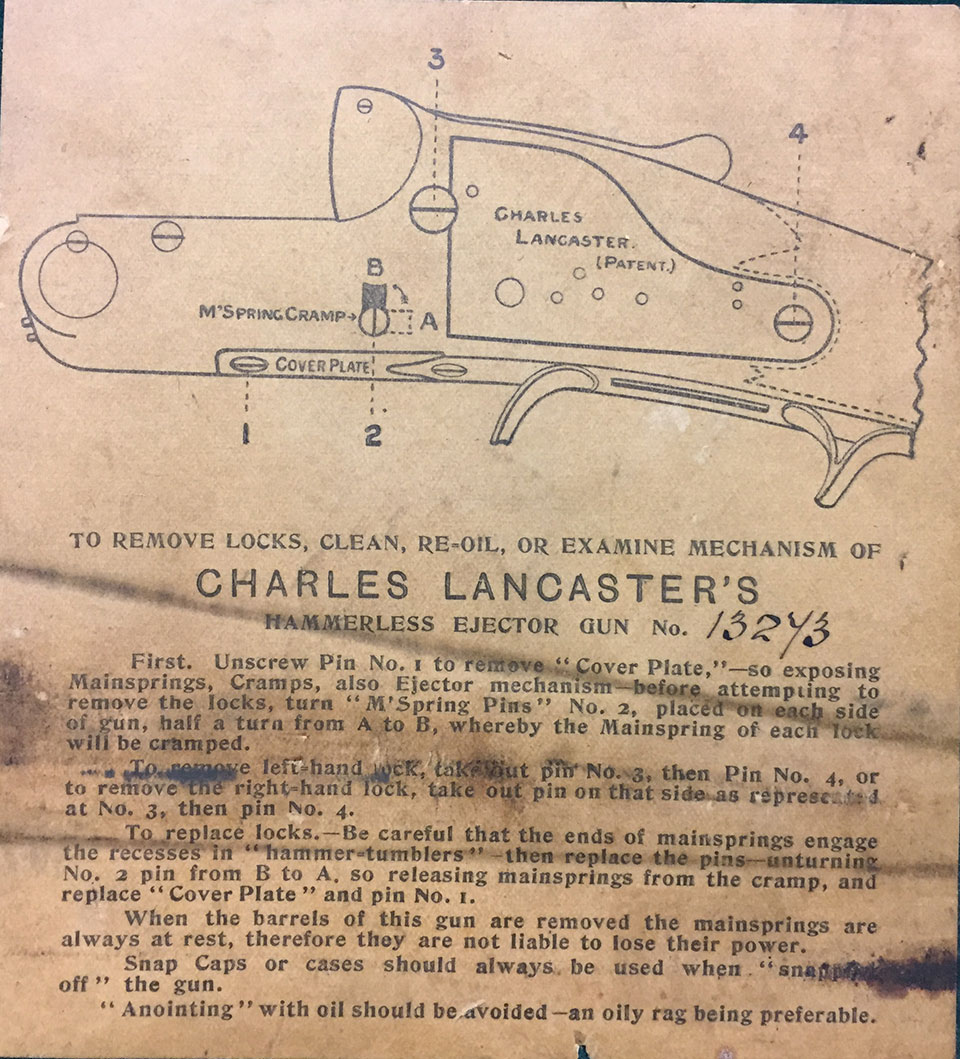

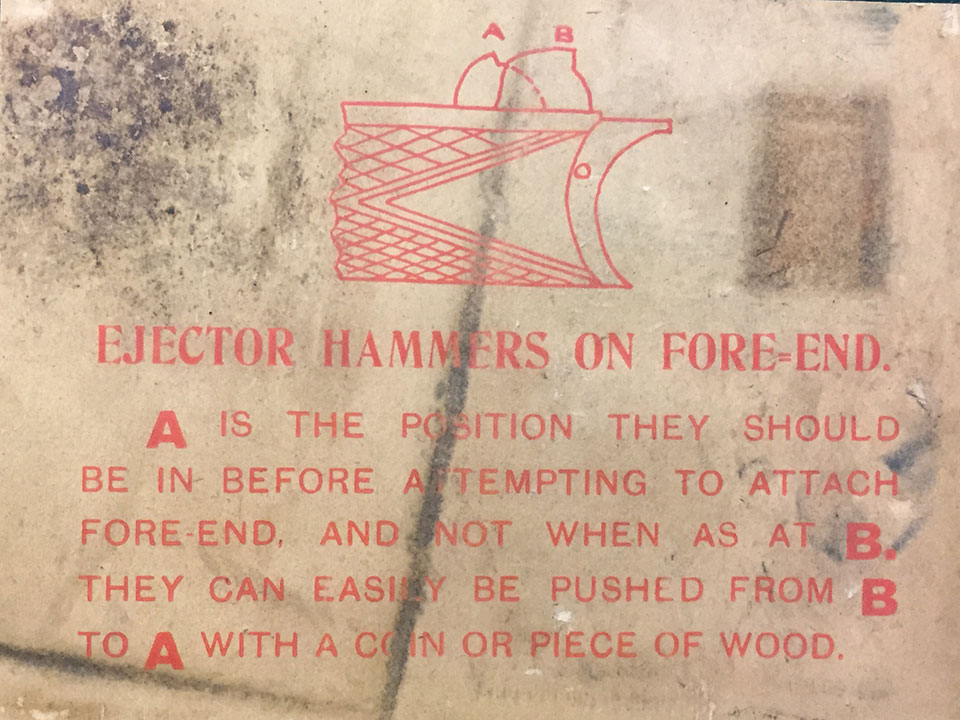

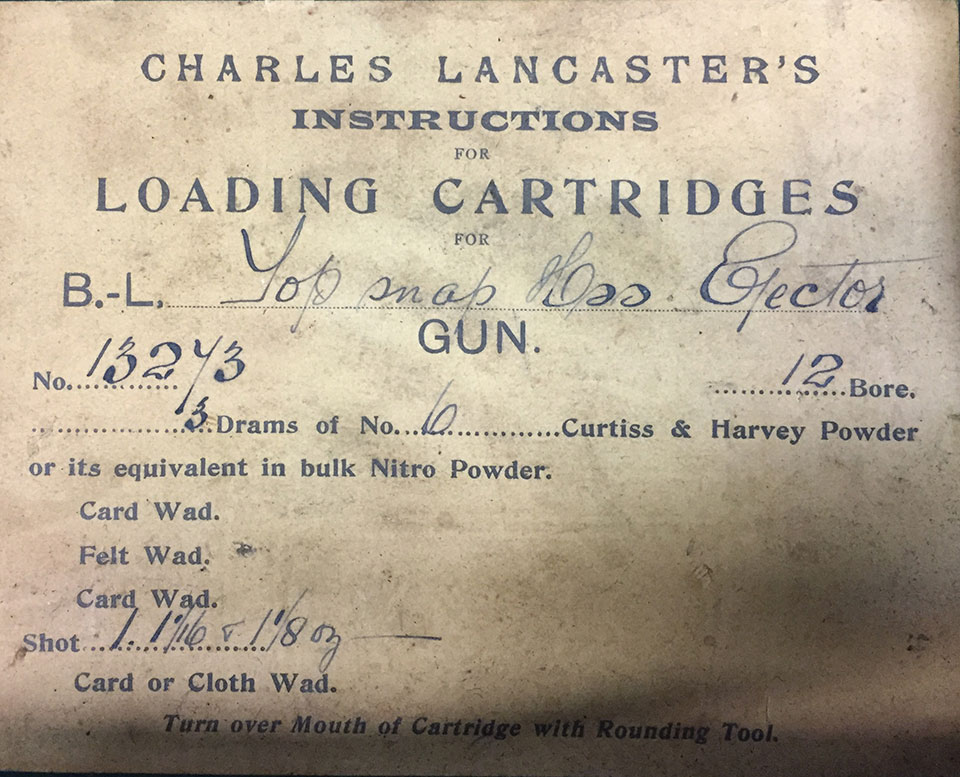

Lancaster advertised ‘Charles Lancaster’s Side-Lock Hammerless Ejector Gun (Patent)’ in 1890, describing it as having a number of attributes, including ‘ejectors perfectly independent of the lock-work’. The advert further claims ‘the locks are cocked before ejecting and no extra force is required to open the gun’.

Like the Beesley/Purdey, the Lancaster’s mainsprings are always at rest when the gun is dis-assembled.The gun jumps open when the top lever is pushed aside and the gape is average for a gun of its day. In my estimation, however, once open, the gun feels sloppy and springy, only tightening up as you close it and tension is restored in the mainsprings.

While on the subject of Frederick Beesley, we should note that the Lancaster ‘Wristbreaker’ is, in fact, a Beesley design. The rights to his 1884 patents (numbers 425 and 14488 of that year) were purchased by H.A.A Thorn, much as Purdey had earlier bought Beesley’s 1880 self-opener, which, one has to admit, was a far greater success and remains Purdey’s side-lock to this day.

Holt’s have offered Lancaster ‘Wristbreakers’ seventy-one times in the last decade; the vast majority selling for under £1,000 and many showing as ‘unsold’. The most expensive one I could find was sold for £2,200, while other Lancaster side-lock models, like the Baker action ‘Twelve Twenty’ regularly made £5,000 or more.

The ‘Wristbreaker’ cost £60 in the 1890s and can be encountered with a single trigger, notably Lancaster’s ‘in house’ mechanism, built on H.AA Thorn’s 1895 patent number 5517. ‘The Field’ reviewed this favourably in June 1895, saying it was ‘a weapon which does great credit to the ingenuity of the maker’.

Readers of last month’s article will remember the detachable side-lock patent of Lancaster’s then director, H.A.A. Thorn, from 1911. Well this could be incorporated into the ‘Wristbreaker action and it was in some later guns. Wristbreakers were built in a range of weights, like most other side-locks. Guns I have encountered have weighed from 6lbs 3oz to 7lbs 6oz.

most simply can’t make a spring like the Lancaster requires

Repair and service is a consideration when buying old guns and I have one American client badgering me to have a new mainspring made for his Wristbreaker. Unfortunately, nobody wants to do the job, most simply can’t make a spring like the Lancaster requires. Practically speaking, if your gun breaks a mainspring, it is dead.

I bought one in auction once, for an overseas client. In the pigeon hide I found it kicked surprisingly hard, even with the 28g loads that my usual Victorian guns soak up nicely. The lock plates made the action, of necessity, high. This profile extends into the wrist and I find the combination of narrow and high less than pleasing and somewhat awkward.

Whether this has any bearing on the felt recoil, I’d have to do some more experiments to verify. What I do recall is the uneasy feeling that the gun was unpleasant to shoot and that, while it was of beautiful quality, with the fit of wood-to-metal and metal-to-metal excellent in every regard, with superb Damascus barrels and lovely wood, I didn’t like it. I remember wanting to like the gun, feeling I should like the gun. But, really, not liking it.

On reflection, I suppose my sentiments rest on a mantra that I use when discussing the hammer guns that are my foremost passion. ‘I have no interest in beautiful guns that don’t shoot’. I have owned some very racy-looking, really beautiful hammer guns in my life, but unless they work in the hands, they don’t stay. As for side-locks, I have never handled a pre-WW2 Purdey that I didn’t like. Conversely, I have never had a Lancaster Wristbreaker that I did. Is it something intrinsic or simply horses for courses?

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on