As breech-loading designs advanced in the mid to late 19th century, most of Britain’s famous firms became recognised for a particular action. Purdey, for example, settled on the 1880 Beesley spring-opener, while Westley Richards focussed on their 1897 hand-detachable lock gun and Greener on his 1880 ‘Facile Princeps’.

The double gun and rifle action most closely associated with Rigby was the product of a collaboration between John Rigby the Third and Thomas Bissell, an actioner who lived in Peckham, about six miles from Rigby’s shop at 72 St James’s Street. Bissell had a ‘gunworks’ in Bermondsey, about five miles from Rigby’s.

It was common in the 19th century for a gunmaker who had invented a good design for a new mechanism to enter into a mutually beneficial arrangement with a wealthier company, who could afford to pay the fees for patent protection. The two would co-patent the design and share royalties for as long as protection lasted (generally around fourteen years).

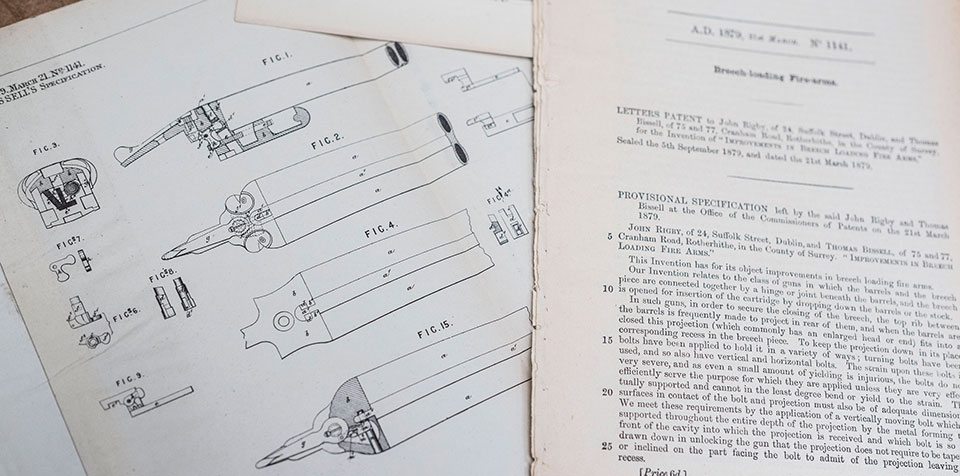

Rigby & Bissell lodged patent 1141 ‘Improvements in Breech-Loading Firearms’ on March 21st 1879 (it was sealed on 5th September 1879). John Rigby gave his address in the patent document as 24 Suffolk Street, Dublin and Thomas Bissell his as 75 & 77 Cranham Road, Rotherhithe New Road.

In the patent, the description refers to a ’vertical bolt’. In Rigby’s records, it is variously listed as ‘Vertical Bolt’, ‘Bissell Action’, ‘Bissell Patent Action’ or ‘R&B Action’. The exact origin of the term ‘Rising Bite’ is as yet unclear. Former chairman, Paul Roberts recalls it as having been in common usage within the British gun trade for at least seventy years.

However, anybody searching Rigby’s records for references to a ‘rising bite’ will not find any. That fact notwithstanding, The ‘rising bite’ became a byword for Rigby’s double guns and rifles for the next half-century.

Mr Rigby & Mr Bissell

Coincidentally, proprietor John Rigby III and gunmaker Thomas Bissell were both fifty years old in 1879, when they co-patented the action for which Rigby would become forever renowned.

Bissell was born in Middlesex in 1828 and christened at St. Brides, Fleet Street, London. He married Sarah Seabrook, ten years his junior, in Lambeth in 1859. Together, they had fifteen children, two of whom, Thomas and Walter, became gunmakers. As was common in the Victorian era, several of their offspring died in early childhood.

Rigby’s relationship with Thomas Bissell began at least as early as 1872, when his name begins to appear in the ledgers. It was long and fruitful and journals from the period contain numerous references to ‘Mr Bissell’, referencing his home address as 98 Hollydale Road, Peckham.

His house still stands today; a modest Victorian end-of-terrace, of two stories, with a small garden, in a residential street. In 1892 Peckham was a prosperous and growing residential area with good links to the city. It was also home to George Bussey’s ‘Firearms, Ammunition & Shooting’ emporium at the Museum Works in Rye Lane and the Museum of Firearms. It was a fitting place for a gunmaker to settle.

Thomas Bissell was a ‘maker to the trade’, or ‘outworker’, though he did make guns under his own name, as well as for Rigby. Examples of other such gun-trade relationships include John Emme’s collaboration with James Woodward, Edwin Hodges’ partnership with Stephen Grant and John Robertson’s services to Boss.

Bissell is first listed as a gunmaker in 1851, when he was twenty-three years old and had, presumably, recently finished his apprenticeship. He first operated his business from premises just across the River Thames from the Tower of London, at 76, Tooley Street, three and a half miles from his Peckham home.

The earliest reference to his presence there dates from 1857. He moved to 75, Tooley Street the following year and to 73, Tooley Street in 1870, staying there until 1875. Tooley Street is an hour’s walk (five miles) from Rigby’s shop in St. James’s Street. In 1876, he also had premises at 30 Star Corner, Bermondsey.

Bermondsey, in the late 1700s, was a prosperous spa town but by the late 19th century was known as an industrial area, with tanning and leather works being foremost, as well as being a centre of calico production. Nearby, were the docks and warehouses, where food was unloaded from all over the Empire. Housing, however, by the latter half of the19th century, predominantly consisted of dreadful slums.

In 1877 Bissell was recorded at 75-77, Cranham Road, Rotherhithe New Road (the address he gave to the patent office in 1879) and he stayed there until 1886; the period during which the co-patent with Rigby was being worked-out. Records then revert to his home address in Peckham, where he was living with his wife and six of his children, in 1891. He died in 1892 of ‘influenza bronchitis’, at the age of sixty-four.

Prior to designing the vertical bolt, Bissell had already lodged patents for a gun with internal strikers and external ‘hammers’, which acted as cocking levers, (No.1461 of 1865). This patent also contains specifications for an extractor, which was quite widely used on hammer guns.

We can deduce from the available information that Thomas Bissell was successful and active as a gunmaker from at least 1851-1891; a span of forty years in the gun trade, after finishing his apprenticeship.

A Rigby journal entry from 1886 shines some light on the nature of the Rigby-Bissell relationship. On 3rd July, it records money paid to: ‘Bissell, T.W. Peckham. Making one R&B under-lever Hammerless action No.2014, lever-catch, under-plate & furniture’ (£11. 18s. 0d), ‘1 pair of Brazier’s best hammerless locks’ (£1. 15s. 0d). It also notes ‘1/2 Royalty on action’ (£1.10s 0d).

From this we can see what actioning work Bissell was carrying out for Rigby. We also know what the Royalty payment due for each gun built on his patent was. If a half-payment was £1.10s.0d, then a full Royalty was twice that figure; £2. 20s. 0d.

Bissell appears in the workshop journals as actioner, stocker and finisher, and the work attributed to him is so varied and voluminous that it confirms he had his own team of gunmakers carrying out trade work from his own workshops, rather than operating as a single-handed journeyman gunmaker. Bissell was clearly a gunmaker of some skill and dependability, for John Rigby to rely on his services to the extent that he did.

The 1879 Patent

This long-standing collaboration between Rigby & Bissell is what spawned the famous patent (No.1141 of 1879). It was dated 21st March and Sealed on 5th September 1879 as ‘Improvements in Breech-Loading Firearms’.

The action, called the ‘Vertical Bolt’ by the patentees, makes use of the Purdey double under-bolt as the primary means of bolting. It is augmented by a rib extension, which slots into the top of the action.

Within the extension is a shield shaped cut-out. A bolt rises from the action, when the gun is snapped closed, sliding upwards to fill the cut-out, thus bolting the gun from the top to create what gunmakers call a ‘treble-grip action’.

Operation was by means of snap-under-lever, side-lever or top-lever and the rising bite can be found on guns with external hammers, early hammerless trigger-plate actions and hammerless side-locks. Rigby even has in its collection one vertical bolt hammer rifle with the Jones rotary under-lever.

When it was sealed, in September 1879, the patent for the Rigby & Bissell action placed it on the market at a time when hammer guns were beginning to give way to hammerless guns, and in which a great deal of innovation was still ongoing. Beesley had not yet patented his famous side-lock action for Purdey and John Dickson’s ‘round action’ did not yet exist. Neither did the second version of the Holland & Holland ‘Royal’.

Rigby’s rising bite hammerless gun, with its distinctive dipped-edge lock-plates must have looked like a state of the art centre-fire breech loader to the public, when it was first demonstrated.

In fact, its impact may be viewed through the lens of a review published in ‘Land & Water’ in August 1889, written by George Teasdale-Buckell, attesting to his admiration for the vertical-bolt: ‘If a top grip is used there is none that can exhibit so many advantages as the Rigby vertical bolt. It is by far the simplest and neatest, doing its work with the fewest pieces of metal and requiring the smallest amount of cutting away of the breech and thus it it leaves the most important part of the gun more solid and the whole gun stronger on that account. Since its principle and action is so true its wearing powers are of high order, whatever wear there may be can be met immediately by simply fitting a fresh pin’.

Continued in Part 2.

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on